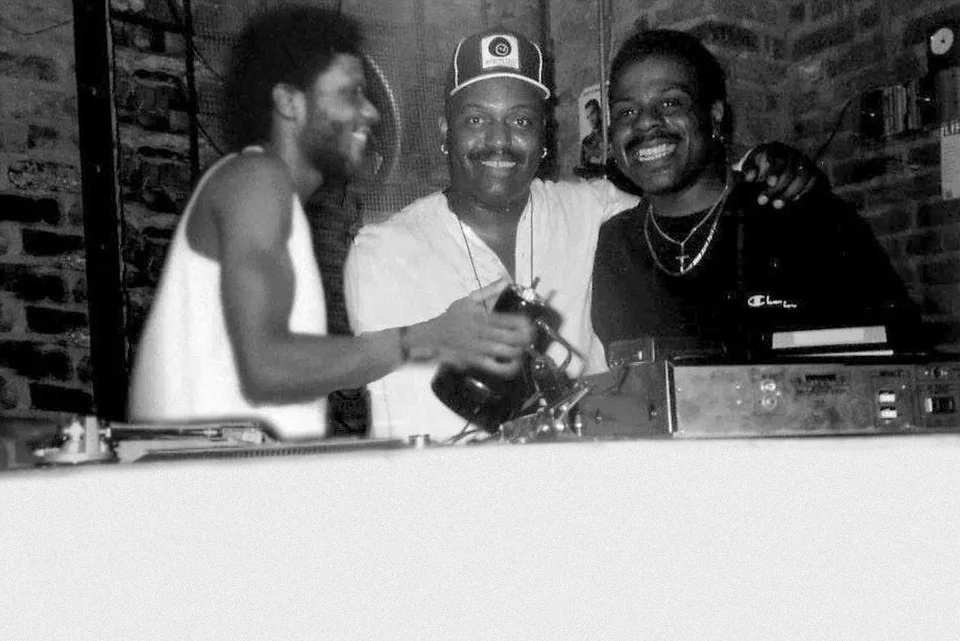

Danny Wang meets Tee Scott

Born in the Bronx, pioneering New York DJ Tee Scott is remembered for his residency at seminal disco party Better Days. No footage of Scott DJing WAS thought to exist; until only recently when film of him playing in Japan was uploaded to YouTube. Scott died from cancer in 1995 and is often named by his successors as a major influence.

Hardly any written interviews with SCOTT have surfaced either, BESIDE FOR A 1994 CONVERSATION WITH contemporary DISCO music DJ DANNY Wang. Here, FIRST WE PRESENT an updated introduction written BY DANNY exclusively for Boy’s Own, AND UNDERNEATH THERE'S his original interview to enjoy alongside the YouTube set ABOVE.

If someone says the phrase ‘greatest female jazz singers’, who’d come to mind? Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald without a doubt. But almost twenty years into this new millennium, some truly original and effervescent voices of the mid-20th century seem to have been almost entirely forgotten.

Let's be blunt, some of their best songs get less than 2000 clicks on YouTube. I am amazed that anyone still listens to Anita Ellis, Gloria Lynne, or Chris Connor (these ladies rank among my favourites), and equally amazed, but no longer surprised, that the blonde blandness of Diana Krall sells millions. We avidly read the glowing commentary below those clips of obscure artists whom we adore, aware that maybe half of it is nostalgia, while the other half acknowledges a level of musical merit which only the passing of time can validate.

But of course, no memory lasts forever. Each generation adopts the icons and heroes which best suit its temperament. How many artistic originators get lost in the annals of history? And does it even matter, because so many of them died anyway before all the praise and money flooded in? History will surely record Levan and Knuckles as the godfathers, and maybe Skrillex and David Guetta among the most popular and successful DJs of all time; but that's why we can be glad for books like Tim Lawrence's Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor, and magazines like Faith to set the record straight.

They help us remember that the realm of electronic music and DJ’ing once had a Garden of Eden (with Adams who loved Adams and too many sinfully delicious fruits on the trees!). This was during a pre-globalisation era, actually not long ago, without hysterical crowds paying £200 a head to hear 128GB USB sticks loaded with dubstep. Like I coincidentally made Tee Scott’s acquaintance before this interview, I imagine meeting Roy Thode or Walter Gibbons on Fire Island. And I think of several gay DJs whom I met in San Francisco and Chicago in the early 90s who hardly play out anymore. Who knows what memories and treasures have not yet even surfaced from that mystical proto-disco moment from around 1967 to 1973?

Personally, I feel profoundly happy when I watch this video of Tee Scott in Japan. It is a modest confirmation of what really matters in DJ'ing. The way he shakes his butt in that groovy, natural way as a physical reflection of what he hears and feels inside -- but also to know that SOMEONE outside of New York had the good taste and knowledge to fly him out, away from that chaotic town where he had lived his entire life. (Geographical immobility is sometimes necessary for creating inner universes.) I can taste that sublime sushi dinner which he surely enjoyed, and imagine the emotions of being in a truly distant land as a welcome foreigner for probably the first time ever. Thank you, our Japanese friends.

Most of all, I am so glad that this detailed interview with Tee Scott has been preserved. But I also confess to astonishment, because in 1994, I was a naive apprentice of dance music who could not have known how important Tee would appear in retrospect, nor that my own life and that of so many others would follow a path similar to his. I think I'm even glad that Tee did not know that he only had two more years to live after our long chat. He was optimistic, and that was illusory. But is not the promise of good times ahead, of love, of travel, of creation, of a fabulous party, the only thing that keeps us all going?

Danny Wang, January 2018

A warm Sunday night in April 1994, I was at the Marc Ballroom in Union Square where the House of Ultra Omni was holding a ball. A few hundred people gradually filled the room. The invite had detailed some fifty or sixty categories of competition, and Paris Dupree, Avis Pendavis, and a host of ballroom legends were preparing their outfits in the hallway. And although the event would go well into the wee hours, the deejay's choice of music throughout the evening was impeccable: these were the bass lines, riffs and loops of Giorgio Moroder's Evolution, Danny Tenaglia's Harmonica Track, Junior Vasquez's Dub Break, plus Philly tracks, Salsoul, and other gems both old and new. But then, this was Tee Scott playing, a New York hero himself on the turntables; and for once, there was the rare chance to make some small-talk and get a phone number. When we spoke, he was vivacious and extremely articulate.

Danny Wang: Hi. Have you got some time to spare right now?

Tee Scott: “Sure! Actually, I was just on the phone for two hours last night with WBLS. I'm getting ready to do an interview with them too, and suddenly everything is happening all at one time.”

Has it been like this for you lately?

“Yes, it was like that for a whole ten year period. It wasn't all interviews, but I was doing studio mix on top of studio mix, I lived in Brooklyn, and then I was doing guest spots at Mellon s, and Zanzibar, and everything at the same time. Mellon's was on 16th Street. It was a club-slash-skating rink; they did some skating during the day. It was on the 12th floor, and that was around 1980. Mike Stone and all of them were doing it, and it was very popular far about two years. It was supposed to be gay, all of the clubs in Manhattan were supposed to be gay [laughter]. But some straight people heard about it, and they wanted to be involved so much that you practically couldn't keep them out. Their clubs weren't like that and they didn't have the kind of excitement that the gay clubs had, with the exotic dancing and the mixed music. And once they got into the gay clubs, you couldn't get rid of them.”

So how old were you when you started out, and what kinds of clubs were you playing?

“Well, this is an old story, but as a matter of fact it reminds me of when you see Bette Midler on TV. They ask her how she started out, and she starts them about the Continental Baths, and then she says ‘God I've told this story so many times!’ My story is really very similar to hers in that way.”

But it wasn't at the Continental Baths!

“Actually, they were part of it. And Bette Midler got started right about the same time I did. I was really into music. I never thought of being a deejay. I used to take my little tape recorder and tapes and pretend that I was a radio broadcaster, and bring in the records while I was talking and all that kind of stuff. I was working for Family Court, and I was working as a telephone operator at EJ Korvette's at night to make some extra money, they're a big chain, like Caldor's, and meanwhile I'd been doing radio broadcasting apprenticeships at WHBI. I had a cousin who was definitely in the (gay) life, and he used to go to a club called Stage 45, located on 45th Street between First and Second Avenue, and he used to drag me there every once in a while. It was all jukebox music, but it was hot, and the club was very popular. I used to sneak in, I was 17 or 18, and this went on for about three years. I was almost 21 when I first started deejaying. So then, when Stage 45 closed, there was this club called Willy’s..."

What kind of music was on the jukebox? Is this the early 1970s?

“Yes, and you're talking about Little Sister’s You're the One and all those things on 45s. There was no mixed music back then. Then I started going to this club called Willy's at 81st and Broadway, which I think were the same owners, and that was still jukebox music. But then my cousin and I wandered downtown, and we found this club called the Candy Store. This club was on 56th Street between 5th and 6th Avenue, and that was the first place where I was introduced to mixed music.”

And who was DJing back then?

“That DJ shall remain nameless as I have no idea. But that was a big part of my life, because when I went in and I heard this guy mixing music, I was very creative, I said wow, this is exciting, so I thought of going there a little more often. Not quite that often, because at that time I still wasn't a club-goer. Then one time, I went down there, and they had somebody else. And I noticed that this guy was not as exciting as the original guy; that's when I found out that there's a definite difference in how people mix music. I couldn't even tell you what I didn't like about it - it was completely like the other guy's, but it didn't have the same flair at all. After a couple of 151 and cokes, I got up the nerve – I was very shy – there was this rumour that they were trying to oust the other guy on some stupid technicality. Don't even know the guy, don't even know anything about him - just wanted to help him out by getting his job back. So I went up to the manager and told him, you know, I don't want to say anything bad about this guy's playing, but I'm sorry, he's just not the same as the guy that you had before. So he said, Oh really? Why don't you come up and tell my boss that? And I said, Uh oh. It was going to go this far. So I went upstairs, and after about 5 minutes he says, Do you play music? And I don't know where that answer came from, but I said Yeah! I had the nerve - I had never mixed or anything before in my life, so he says, Why don't you come for an audition? At that time I didn't have a lot of records, only from my personal collection. This was like early '72 - so I went down three weeks in a row for this audition, and every time I went down there was always some reason I couldn't get on. The final time, I went down, I waited around, and he says: I can't put you on tonight, so why don't you go to the bar and get a couple of drinks? By this time I was pissed. And I said, I didn't really want to do it anyway, I was being pushed into it by my cousin. We were getting ready to leave, and I said to hell with it, let me go drink up this man's liquor! So I got behind the bar and got a couple of drinks. All this is like fate, because while we were sitting at the bar, this guy who was the manager came up and tapped me on the shoulder and says, My boss wants to talk to you, he sent me out to see if you were still here. So I went, and he said, Can you still do that thing? I can get you on tonight for about 15 minutes. So my heart started pounding, and he showed me to the deejay booth. It had a real, real old-fashioned mixer, and the only thing I knew about that mixer was phono one and phono two. No headphones, I didn't know where to put them. But see, I'd done electronic engineering in trade school, so figuring it out was no problem for me. In 5 minutes I figured out how it operated; I just didn't have any skill in operating it. I saw the word Cue, and I realised this is how you pre-cue. Believe it or not, I had about a handful of albums and about three or four 45's. And about 10 minutes left. I started playing, and it caused such a reaction downstairs – the deejay booth was upstairs – that people came running up to find out who this guy was. I ended up playing 45 minutes that night instead of the 15, and the manager said to me: I'll be in touch with you.”

Do you remember what those records use?

“Oh God, I can't even… I know one of them was Papa Was a Rolling Stone… No , that wasn't even out yet. I can't even remember what they were! A couple of Temptations, old stuff; I know one of them was Black-Skinned Blue-Eyed Boy. Anyway, about 3 weeks after that, I was walking out of my house, and the phone rang, and I was trying to make up my mind whether to go back and answer the phone. I did, and it was the guy asking me if I wanted to start work on Thursday. This was Wednesday, and I said, ‘Sure!’ I was there from May of '72 until July of '72. What happened then was another twist of fate: this customer who liked my music so much – he used to just come down and praise me and praise me – at this time this other club called Better Days had opened up with a lesbian deejay. Willy's had closed. They were having a lot of problems with the cops because they had such a big crowd and all that, and the owners bought Better Days. At that time it was jukebox half the night, and they were just starting out with this deejay. Her name was Bert. My cousin went there a lot. I was basically playing once or twice a week at the Candy Store, and I was never around gay people that much. I didn't even know there were that many gay people in the world."

Who would have known?

“Right! And I was never a big crowd person. I'd always wanted to be popular, but I was too nervous. So my cousin would tell me: Tee, you gotta come down here, you gotta come down here, yeah, okay, okay. I was always an independent person: I had my own car, and I was just going in different circles. Eventually, this customer came and told me his name is John, I'll always remember that, and said, "You ought to go over to Better Days; they're looking for a new DJ."

So I went there, and it was real strange, because when I talked to the manager he said: Who told you I needed a new deejay? I said it was this guy who used to come to my place. He said: This is real strange, because we were not looking for a new deejay. But what had happened was: the night before I finally decided to go there, the deejay who was there did a real no-no with the boss' wife. The boss' wife had asked her to play a request, and Bert told her, No, I don't play requests. And the woman said: Do you know who I am? And the deejay said, I don't give a fuck who you are, I don't play requests! That was the end of her job! And this happened the night before I came up. So he says, Why don't you go in and do an audition, and we'll see how you are? I went into the deejay booth, and it was real, real, crude. I had to climb up onto this thing; it was unbelievable. There was no such thing as a pre-cue. What they had was a Sony amplifier with a phono one and phono two button, and that's how you switched from turntable to turntable. No fading, nothing.”

What was the club like in those days? How were the floor and the lights?

It was a large dance floor; the lights were very basic at the time. They had this automatic light panel, and lights over the whole ceiling. You could change it to, like, six or eight different patterns: a red ring, a blue ring, and a green ring, like a bullseye. And there was a big board on the wall inside the deejay booth, but it wasn't working when I first started working there. I had to cajole the manager and owner into getting somebody in the there to fix that board - it was there from Year One Disco, back in the 60s. It just lit up, but it wouldn't go through any of the patterns or anything. Talk about primitive. They had a jukebox on in the day, since they opened at 3 or 4 in the afternoon, and I would come on at nine or ten o'clock at night. I would play from ten till about four; the bars at that time closed at about four o'clock. I thought that I'd gotten the job, but when I came in the next day to play, he said, Nobody told you you were hired! So I struggled through that night with no headphones or anything, and then I went home and designed, and brought in this little amplifier and headphone thing and plugged it in so I could had pre-cue.”

Possibly the only deejay ever to build your own mixer.

“And then I started on the light system, and the boss was so cheap he didn't want to put it in, and I would go and buy the materials with my own money and put it up myself, and eventually he would pay me and do it the right way. You know, in the electrical sockets and all that. I was running these with AC line chord - I would go buy hundreds and hundreds of feet and put it up on this very high ceiling, and run the wires into the deejay booth, so I could have a flash of light, and a red circuit and blue circuit that would light up the whole room. He didn’t want to spend money for boomers or tweeters, so I went out and made two clusters of tweeters, and ran the wires myself to make the sound better, and eventually I wound up getting Alex Rosner to do it. He was one of the main competitors for Richard Long, although not quite as good. Rosner put in the very first disco sound system; that was at the Gallery, with Nicky Siano, back in '74 or '75. So meanwhile, the Gallery was opening, the Loft became popular - that was with David Mancuso - and these were after hours clubs that didn't open until 12 o'clock and didn't close until 7 or 8 in the morning. They had these fabulous sound systems, I had this rinky-dink sound system, and it was a constant tug of war with customers. When people started going to the underground clubs, Better Days was a bar-club, and these other clubs were open all night. I had to compete with them, and I had to diligently start improving my sound system and my music: I made it so that when you came into Better Days, you started dancing from the time you got in there, and you did not stop until you gat out of there. And not only that, but Better Days was known as a gay, black, militant club.

What do you mean by 'militant'?

“It was rough – street rough. Or that was the way people looked at it. And there no such thing as a white person, or an Oriental person, or a Spanish person coming down to Better Days. It was known to be black. I endeavoured to change that. I started inviting all kinds of people down there; I had to go rub elbows with all the record companies, because at that time, John Brown and other people - John Brown was like, the head of Capitol Records, and I think he is at Virgin now, though at that time he was working for Elektra Nonesuch; and Larry Patterson, who is a well-known deejay in New Jersey -they kind of took me under their wing and told me, Tee, you have an excellent reputation, but nobody knows what you look like! Because I was always so shy, and because the first 3 years I was working at Better Days, I was also working at Family Court from 9 to 5. Then, I d go to work at Better Days from 9 to 4 at night. It was rough. See, this is how the Baths come in: Continental Baths was getting popular around the time I started at Better Days. Larry Levan was just getting started at that time; Frankie Knuckles was also trying to get started.”

But he ended up in Chicago.

“Well, I'll tell you how he ended up in Chicago. I kind of knew Frankie through various channels, but we became friends during this club boom, and Frankie was trying to play at the Continental Baths. So one night I saw him sitting there with his head in his hands, and I said, I'm overworked with seven nights a week over at Better Days, so why don't you have two of my nights there? I gave him Monday and Tuesday; he worked there for six months a a year or so, and then he got an offer from Chicago, and I gave the job to somebody else. So I was the one who gave Frankie his first job, and if you ask him, he'll tell you. We're still good friends. As a matter of fact I'm sitting here looking at his record cases from when he went to Japan about three years ago.”

Have you got enough room for all your records?

“I'm being run out of my house by these records! And I've still got 15 crates at a friend's house that I haven`t been able to recover, all my classics and stuff. It is hard moving around. When I moved to Jersey from New York, I left most of my records at his house. My house is full of them, and they're going to stay there: I've never been desperate enough to have to sell them. I couldn't sell such a key part of my life. I've known people to do it, but I couldn't. When I finally die, I'll probably will them to somebody. But basically, that's how I became a deejay. And going back to Better Days, I had to go to the record companies and let people know who I was, and I got involved with people like Dan Joseph from TK Records, and Polydor Records, which at that time was David Steel, and once we made friends, they started coming down and bringing their friends, white guys, and they realised that they didn't have to be scared when they came down to Better Days. And the reputation was like, 'Better Days is rough, people get beat up' and all that, but when they came they saw that it was just a heavy-partyin' club. Eventually, the club became very well-blended, and then of course straight people started coming down.”

And the other places you played, like...?

“I didn't play at Tracks; only later on, maybe. Andre Scott was a good friend of mine whom I'd met through Larry Patterson and all them, and Andre used to run the Clubhouse down in D.C. So I played there, and in Baltimore, and I got invited to play at L'Uomo out in Detroit. This was all '75 through '80-something. I'm still kind of deejaying, but I'm not doing it as a living at this point. I stopped in ’92."

And why did you stop?

“For several reasons. It wasn't as lucrative for me. I had cancer; I'm a cancer survivor at this point. I came pretty close to death, and a lot of people thought I had AIDS. I was getting skinny and all that, and when I got cancer, I was working at the Cheetah club in New Jersey.”

Zanzibar had that tiger on their sign.

“Yes. For a couple of years I was also doing regular guest spots there on Saturdays, and then I worked at Better Days during the week. Tony Humphries wasn't there yet - we brought Tony Humphries in; he was on the sideline at the time, like Frankie Knuckles, waiting to get in. My life connects with all of them, and this is why I have such loyalty to all of them. At that time, Larry Levan would also play at Zanzibar. Larry and I had the best relationship; we were constantly being pitted against each other as the two best clubs: Garage and Better Days. It was a toss up supposedly as to who was number one, but we ourselves didn't allow ourselves to be put in that position. The media did so, and Larry had the bigger club, which was a tremendous vehicle, so he got more recognition. But for a while we were the only two in the market doing mixes, and it was like, Larry Levan's in the studio! Tee Scott's in the studio! And the companies called us up alternately. We were very close; there was nothing I wouldn't do for him, and nothing he wouldn't do for me. I could bring 20, 25 people into the Garage, no problem. I'd go dance on his dance floor, and he'd come to Better Days and dance on mine!”

So how do feel about club life has evolved over the past 20 years?

“I love what they did, I hate what happened to them. Real clubs have all but disappeared, really. First, there ain't hardly any of them there. You got one or two clubs that are doing really well, but there are no more ‘disco clubs’ or ‘dance music clubs really. Sound Factory Bar and a couple of others, that's it!”

And the music?

“Well, now there's a problem too, because the music started becoming so redundant; there are so few pieces that come out now that are original and that stand out. If you put on record after record of dance music, they all sound so much alike. And most of them are taking samples of something that had already been done and adding a little to them, but nothing is coming out that's really original. You get the Michael Jacksons of the world, or the Stevie Wonders who put out something every once in a while, but all this synthesised music comes out now, and in a couple of weeks it's gone. They're still playing the music they made back then – Love Is the Message, First Choice Choice, Roberta Flack, all that stuff is still classic. What's out today, with rare exception, they're popular for a minute, and then they're gone.”

Obviously, you're interested in going beyond dance music.

“Yes, all music beyond dance music. I was brought up with jazz, and contemporary jazz: my father used to play things like Ella Fitzgerald, Nina Simone, all that. My father was a piano player, and he used to sit down and play Bach, Beethoven... He also had a substantial record collection, and he used to play Nat King Cole... In fact, I have a box of his records here that I pull out once in a while and play. Ah! I loved it. And I also incorporated that into my club music. Nicky Siano, Larry Levan and I used to go shopping and pick out things like Lansana's Priestess by Donald Byrd (on the Street Lady album), and Grover Washington, and we'd put those on in the club - records that weren't popular , that other deejays never even thought of playing. That was all because af our vast interest in music other than the mainstream. I never was a Top 40 player. I touched on some of what became Top 40, but I was never a person to just play what was on the radio, and that's how we gained our reputation. When I first started, we used to play a lot of Latin and a lot of slow records. We had three sets a night for slow records!”

And would people slow-dance together?

“Oh, yeah! I will tell you, there was a funny time, when a couple of my straight friends would come down to the club, and they would kind of follow and get used to it when they were dancing fast. And then at around 11:30 or 12, I'd reach a crescendo with the music, and then bring in something slow - and oh, they used to dance slow! Yeah, very much so! And I would turn around and watch those faces as they saw these two guys dancing together, like Holy cow, they do that too? Well, the clubs really got away from that, and I started playing two slow sets, and one slow set, and then I finally moved into none at all. Because at underground clubs, they rarely - every once in a blue moon they'd shock everybody and play a slow record, but mostly they didn’t."

Now, as for some of the records that you mixed, on Salsoul for example…

“I sat down and wrote a list once, and I stopped at about 140. I did so many that I don't even remember. I'll tell you; I lived in the studio. And when I wasn't in the studio, I was doing tapes for WBLS. And oh! First Choice was my very first mix. I went into the studio completely by myself, and that was Love Thang. And when I went in there, I had been in a studio before, because I did this record in training with Edwin Birdsong. It was really strange, because I thought all I was going to do was edit; I did not realise that I had to take this 24-track record apart and re- design it. I did it, and you know the way it came out. I first went in with the owner of Blank Tape Studios, Bob Blank, who ended up working with Arthur Baker later on, too. Then I branched out into not only doing mixes, but doing production, like "Tee's Happy" or what was it called? I did a mix called Tee's Right with Arthur Baker. And actually, this is funny, but I started the whole 3-turntable thing too, and the naming of the mixes on 12"s. Tee's Happy, Tee's Right, Tee's Groove: I was the one that gave names to them as a little joke. And when people saw that, they started doing all those things like "Roger's Medley Groove" and all that. I was still working at Better Days, and I had 2 turntables. And I wanted to add some effects: I wanted to have a thunderclap or a storm going while I mixed into another record, and I needed either another tape going, or a turntable. So I built a shelf below my regular turntables - their booth was so tiny -- and I brought one of my own record players from home, disabled the automatic thing, and used that as my sound effects table. And I had such success with it on the first night that I ran down to the Gallery and told Nicky, You've got to try this! And Nicky said, I wanna do it too! Next weekend, when I went down to the Gallery, Nicky had already bought another turntable and stuck it up in the corner. And then we went down and told Larry about it at Soho, on Reade Street, Garage wasn't open yet, and that's how it came about! And getting back to the mixes with Arthur Baker, I had to practically re-write that record, Happy Days; it became very popular. Do you know it? (Tee starts singing.) Hold on, you wanna hear a piece of it over the phone? ("Sure," I say; he plays the record, a soulful, uptempo groove somewhat similar to a sped-up version of Good Times.)”

Who was the vocalist?

“Michelle... When I have to remember something, my memory just goes out the window! She came out with another record called Jazzy Rhythms; maybe her name is on the record. Michelle Wallace! I had some friends play the guitar. That was all post-production: I took it apart and put everything on that record , including drums. That record sounded like a piece of garbage when I got it! I sort of became known as the repairman in the industry; I could take any old piece of crap, which I got tired of getting after a while, and transform it into a hit. If I could ever dig up that tape one day and show you what that record sounded like when I first got it... I wrote the drum line, the bass line, the synthesisers.... It sold a lot of records, and I did a very creative instrumental on the other side called ‘Tee's Happy.’ It's been popular ever since: I still get requests for it when I play now. The follow-up to that was called ‘It's Right’: (he sings) "I know that it's right - for me," and I did a really creative instrumental on that. I designed them so that you could start on the instrumental, segue-way into the vocals and never miss a beat, like putting velcro on both sides so that the record was like a reversible jacket - sometimes, vocals are hard to deal with in clubs, since they can mess up the energy if they're not the right kind of vocals - so I designed it so that even non-deejay deejays could do it. I've kind of enjoyed knowing that a lot of the industry was affected by me, because I'm not so well-known except to the people who were involved in it... I see people taking credit for things on TV, and I say, that bitch don't even know where that shit really came from! I'm not trying to blow my own horn or anything, but I see people talking about what they did, and I think: they don't even know where they got that idea!”

Who was Began Cekic? And what was the deal with those grungy little One Way Records that you mixed? He made that version of Love Is the Message where he seems to be playing the keyboards himself.

“Began Cekic was a real case. He was a Yugoslavian guy with this little record company - One Way was a subsidiary of his main label, BC Records, which he eventually changed to One Way. He was the king of the copiers. He got a hold of me, and he treated me to all kinds of baubles (laughter); he bought me two huge 1500s, or 1520 tape decks, the model they used in the studio with a ‘Store’ feature and the extra sections for your tone generators, which were built-in; it cost about $4000. And then he bought me the 1506, which was a 4-track recorder. These were all gifts for doing those records for him.”

So he was the original bootlegger, so to say? Did he make money?

“He made a lot of money on those! He did Love Is the Message, Sixty-Nine, Eighty-Eight, Beyond the Clouds, Relight My Fire, Computer Games, all of those... He took me to Florida, too. Of course he did cover records, really because he didn't sample anybody else's records, it wasn’t possible then. He just did things that sounded close to them. And after a while, he started getting involved in stuff that I felt I should back out of. He started getting really ridiculous and stepping over the line with a lot of stuff. I lost touch with him after a while.”

You know, we've been talking for quite a while now.

“See, I knew that this was going to happen; there's so much involved, because I've been a deejay for over 20 years! I just hope it's okay on your phone bill.”

I'm not worried about that; I'm more worried about typing all this up! Just let me get this tape here, I just talked to Francois Kevorkian.

“Now Francois fits into this whole thing too: he was a very good friend of ours throughout this period. We're all connected, like an old club. Francois and Larry became very good friends, and they, and Nicky, and I all kept in touch. People tried to pit us against each other, but they couldn’t. Larry was always rebellious and had a way of his own, and when Michael Brody wanted to teach Larry a lesson, there were only so many people who could play at the Garage and get over. If he threw just anybody in the Garage, he'd lose money. So he would ask me if I'd do something, or whatever, and I told him: the only way I m going to play the Garage is with Larry's blessings - you can't get me to do anything behind his back. If you have a problem with Larry Levan, you have to straighten it out with Larry Levan. Deal with him directly, don't try to use us. They gained a respect far us, because we didn't let anybody come in and talk to our bosses and undercut us; that's why we're still such good friends today. And the new deejays didn't have that kind of loyalty: they'd cut each other at the drop of a hat. But we didn't have that competition type of thing. It wasn't like that at all.”

And what are you doing these days?

“Well, I left the Empire Skating Rink because I got sick, with the radiation and all that stuff, and I had to give up a lot of my work. Once you’re out of it, it's really hard to get back in. And during this time, clubs were diminishing, so a good job was very hard to find. I'm getting older too -- I'm 45 now, and when I got cancer I was 41. I was losing my enthusiasm for the actual playing because hip-hop was becoming so popular, and there weren't so many dance clubs around. I still had a deep interest in doing studio production, and I also realised that I had been out of the electronics part of it all, which had become so sophisticated. On one mix I found myself going into the studio and not knowing what the hell was going on. I like to be on top of all that, so I made up my mind to learn about all the new equipment... Right now I'm working a security job to pay for it, so its an 8 hour job at night, and then 5 hours of school during the day. It's rough. I'm due to graduate May '95, and I've had a couple of job offers already, but I've chosen to wait until I get out with full knowledge of all this. Because how I got my job as a dejay in the first place was knowing how to repair equipment even while working on while I was playing records, I'd jump down and change a bass amplifier and all. I really like to know how things work,and when you know how things work, you can get the best out of them. I know that whatever I eventually do I'll do well. That may sound big-headed, but I've always gone and done what I believed in doing and come out on top. I had a bad case of pneumonia for a couple of months and a small relapse of the cancer, but we caught that in time, so I'm still cancer-free. It's over now, but I have to keep a constant check on my health. But as long as I keep the positive attitude that I have, I know I'll do well. I have a 3.7 average in my classes so far, and I'm going for it when I get out in May!”

Well, on that note..!

DJ Danny Wang who conducted this interview wears Boy's Own 'Viva Acid House' T-shirt on sale now!